A virtual function is a member function in the base class that we expect to redefine in derived classes.

For example,

class Base {

public:

void print() {

// code

}

};

class Derived : public Base {

public:

void print() {

// code

}

};

The print() method in the Derived class shadows the print() method in the Base class.

However, if we create a pointer of Base type to point to an object of Derived class and call the print() function, it calls the print() function of the Base class.

In other words, the member function of Base is not overridden.

int main() {

Derived derived1;

Base* base1 = &derived1;

// calls function of Base class

base1->print();

return 0;

}

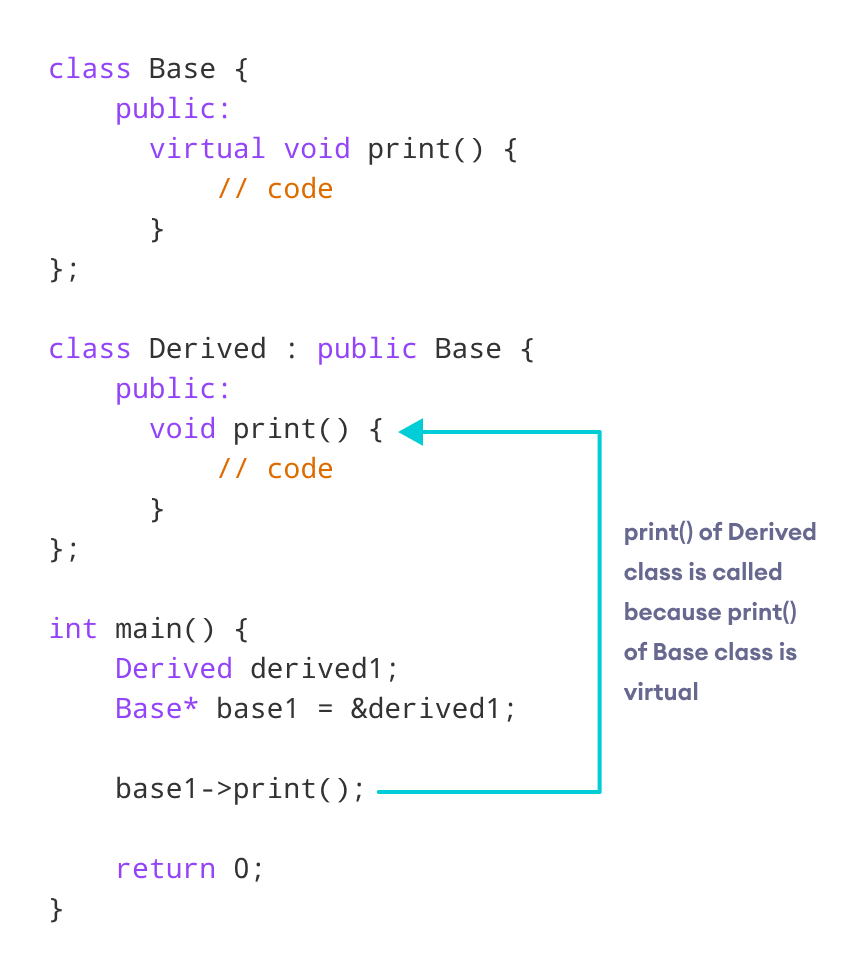

To avoid this, we declare the print() function of the Base class as virtual by using the virtual keyword.

class Base {

public:

virtual void print() override {

// code

}

};

If the virtual function is redefined in the derived class, the function in the derived class is executed even if it is called using a pointer of the base class object pointing to a derived class object. In such a case, the function is said to be overridden.

Virtual functions are an integral part of polymorphism in C++. To learn more, check our tutorial on C++ Polymorphism.

Example 1: C++ virtual Function

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

class Base {

public:

virtual void print() {

cout << "Base Function" << endl;

}

};

class Derived : public Base {

public:

void print() override {

cout << "Derived Function" << endl;

}

};

int main() {

Derived derived1;

// pointer of Base type that points to derived1

Base* base1 = &derived1;

// calls member function of Derived class

base1->print();

return 0;

}

Output

Derived Function

Here, we have declared the print() method of Base as virtual.

So, this function is overridden even when we use a pointer of Base type that points to the Derived object derived1.

C++ override Specifier

C++ 11 provides a new specifier override that is very useful to avoid common mistakes while using virtual functions.

This override specifier specifies the member functions of the derived classes that override the member function of the base class.

For example,

class Base {

public:

virtual void print() {

// code

}

};

class Derived : public Base {

public:

void print() override {

// code

}

};

If we use a function prototype in Derived class and define that function outside of the class, then we use the following code:

class Derived : public Base {

public:

// function prototype

void print() override;

};

// function definition

void Derived::print() {

// code

}

Here, void print() override; is the function prototype in the Derived class. The override specifier ensures that the print() function in Base class is overridden by the print() function in Derived class.

If we use function prototype in Derived class, then we use override specifier in the function declaration only, not in the definition.

Use of C++ override

When using virtual functions, it is possible to make mistakes while declaring the member functions of the derived classes.

Using the override specifier prompts the compiler to display error messages when these mistakes are made.

Otherwise, the program will simply compile but the virtual function will not be overridden.

Some of these possible mistakes are:

- Functions with incorrect names: For example, if the virtual function in the base class is named

print(), but we accidentally name the overriding function in the derived class aspint(). - Functions with different return types: If the virtual function is, say, of

voidtype but the function in the derived class is ofinttype. - Functions with different parameters: If the parameters of the virtual function and the functions in the derived classes don't match.

- No virtual function is declared in the base class.

Virtual Destructor

When a derived class involves dynamic memory allocation, we have to deallocate the memory in its destructor.

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

class Shape {

public:

Shape() = default;

virtual double get_area() const {

return 0.0;

}

~Shape() = default;

};

class Square: public Shape {

private:

double* length;

public:

Square(double len = 1.0): length(new double{len}) {

}

double get_area() const override {

return *length * *length;

}

~Square() {

delete length;

cout << "deleted length." << endl << endl;

}

};

int main() {

// Pointer to Square class pointing to Square object

Square* shape1 = new Square(1.5);

cout << "area of square: " << shape1->get_area() << endl;

// invokes Square class destructor

delete shape1;

// pointer to Shape class pointing to Square object

Shape* shape2 = new Square(2.5);

cout << "area of square: " << shape2->get_area() << endl;

// invokes Shape class destructor

delete shape2;

return 0;

}

Output:

area of square: 2.25 deleted length. area of square: 6.25

When we delete shape1 which is a Square* pointing to a Square object, the destructor of the Square class is called, which deletes the dynamic memory acquired by the Square object.

However, if we delete shape2 which is a Shape* pointing to a Square object, the destructor of the Shape class is called, which doesn't deallocate the dynamic memory acquired by the Square object.

If we declare the Shape class destructor as virtual, the Square class destructor is called when we delete a pointer to Shape class pointing to a Square object.

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

class Shape {

public:

Shape() = default;

virtual double get_area() const {

return 0.0;

}

virtual ~Shape() = default;

};

class Square: public Shape {

private:

double* length;

public:

Square(double len = 1.0): length(new double{len}) {

}

double get_area() const override {

return *length * *length;

}

~Square() {

delete length;

cout << "deleted length." << endl << endl;

}

};

int main() {

// Pointer to Square class pointing to Square object

Square* shape1 = new Square(1.5);

cout << "area of square: " << shape1->get_area() << endl;

// invokes Square class destructor

delete shape1;

// pointer to Shape class pointing to Square object

Shape* shape2 = new Square(2.5);

cout << "area of square: " << shape2->get_area() << endl;

// invokes square class destructor

delete shape2;

return 0;

}

Output:

area of square: 2.25 deleted length. area of square: 6.25 deleted length.

Use of C++ Virtual Functions

Virtual functions are useful when we store a group of objects.

Suppose we have a base class Employee and derived classes HourlyEmployee and RegularEmployee. We can store Employee* pointers pointing to objects of both the derived classes in a collection of Employee*.

We can then call the virtual function using Employee* pointers. When we call the virtual function using Employee* pointers, the compiler invokes the function as defined in the respective derived class.

// C++ program to demonstrate the use of virtual function

#include <iostream>

#include <vector>

using namespace std;

class Employee {

private:

string first_name;

string last_name;

public:

Employee(string fname, string lname): first_name(fname), last_name(lname) {

}

string get_full_name() {

return first_name + " " + last_name;

}

// virtual function to allow overriding

virtual void print_wage() {

cout << "The employee's wage structure is not declared yet" << endl;

}

// virtual destructor

virtual ~Employee() {

}

};

class HourlyEmployee: public Employee {

private:

double hourly_wage;

public:

HourlyEmployee(string fname, string lname, double wage_per_hour): Employee(fname, lname), hourly_wage(wage_per_hour) {

}

// overrides the function and provides proper implementation

// according to the wage structure of HourlyEmployee

void print_wage() override {

cout << "The hourly wage of " << get_full_name() << " is " << hourly_wage << endl;

}

};

class RegularEmployee: public Employee {

private:

double monthly_wage;

public:

RegularEmployee(string fname, string lname, double wage_per_month): Employee(fname, lname), monthly_wage(wage_per_month) {

}

// overrides the function and provides proper implementation

// according to the wage structure of RegularEmployee

void print_wage() override {

cout << "The monthly wage of " << get_full_name() << " is " << monthly_wage << endl;

}

};

int main() {

// declare a vector to store Employee* pointers pointing to dervied class objects

vector<Employee*> employees {new HourlyEmployee("John", "Doe", 13.5), new RegularEmployee("Jane", "Smith", 3000.7)};

for(Employee* employee: employees) {

employee->print_wage();

}

return 0;

}

Output

The hourly wage of John Doe is 13.5 The monthly wage of Jane Smith is 3000.7

Here, the base class Employee has a virtual function print_wage(). The derived classes HourlyEmployee and RegularEmployee have their own implementation of the print_wage() function.

We have stored the Employee* pointers pointing to HourlyEmployee and RegularEmployee objects in a vector.

vector<Employee*> employees {new HourlyEmployee("John", "Doe", 13.5), new RegularEmployee("Jane", "Smith", 3000.7)};

We then used ranged for loop to iterate through the pointers in the vector.

for(Employee* employee: employees) {

employee->print_wage();

}

Here, employee->print_wage() invokes the print_wage() function based on the type of object that the pointer employee points to.